1. The Pheasant

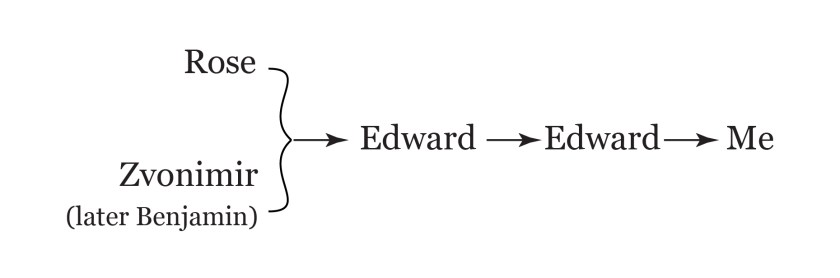

This time, the path to my great-grandmother’s long-gone garden in Detroit starts at mine in Chicago.

We are blessed to have a city home with a large backyard, and a neighbor who keeps it filled with plants and flowers. We also have a kitchen door with four little windows, perfect for enjoying the whole view of the yard and the alleyscape beyond.

One day last year I was at the door, when I saw a brown rabbit in the garden bed. This happens a lot in the city. We two were having a quiet moment—me the hidden watcher, while this unaware bunny hopped between the dahlia stalks.

And then I thought: I bet the pheasant happened like this.

If you hang around my family long enough, eventually you’ll hear The Pheasant Story. There are several versions, and we all insist we know the right one.

At base, the story is that my great-grandmother Rose once killed a pheasant with a broom. Sometimes the bird is injured when she sees him—a mercy killing. In other tellings, the bird is fine but merely unlucky to end up in her sights. You’ll hear that he was turned into dinner, or that he was mounted on a stand that sat atop the china hutch, or both.

Story stacked on story, with the truth somewhere in the overlap.

I remember seeing a mounted pheasant on top of the hutch. For decades he lorded over two different dining rooms in Detroit. In my memory he looks taxidermied—not like patched-up kitchen scraps. However, I know that Rose was too practical to turn down free meat. So he probably was dinner.

At the least, it’s fun to picture her chasing a bird, broom overhead, around the garden of their Hull Street home. We love that image.

Whether Rose would have killed a bird with a broom?

That is not even debated.

2. Gramma

It’s taken me three years to write this part of the Hull Street story, and not for lack of want. I’ve wanted to talk about Rose, very much, and often. I can’t write the house’s story without her.

But I’ve hung back. Roses are fuller for their layers, and she was a complicated person. I once described Rose as unsentimental, and my aunt gently redirected me saying, “No, she could be very sentimental.” And she is right: Rose not only loved, she loved earnestly and hard, sometimes to a destructive fault.

Not all the memories of her are good ones. But there are people who love her even today—me included. If the truth is where our stories cross, that’s very much where she stands: at the intersection of beloved grandmother and difficult, unyielding woman.

Nothing about her was physically imposing. Rose was barely 5 feet tall by the time I knew her, already in her 80s. Arthritis had set her fingers at a 30-degree angle. And yet, if you had asked me who was more powerful–my dad, or my great-grandma–I would have struggled to answer. My dad was the strongest person I knew, but Rose’s power was something other. People deferred to her. If all the grownups in the family each had one vote, Rose had 1.5 votes. When she was mentioned in conversation, her name weighed more than other people’s names.

Rather than unsentimental, I think a better word for Rose is… unsparing. Whatever life required of her Rose gave it—and in bushels. Whether it was work, or love, or feeding her family, or her devotion to the Croatian Lodge, she gave it everything. If work was never-ending, neither was her effort. Nothing was spared.

But by the same token, for people she didn’t like, people from the wrong ethnicity or race, people she thought had betrayed her, and even sometimes for people in her sights who just seemed vulnerable… she also gave them everything, and it could be terrible.

3. The Pest

I was never scared of Rose, but I was always slightly awed, and curious in the way unusual people make you curious. With youthful eagerness I tried getting stories about her life, only to run up against Rose’s legendary stubbornness. It was all sad; no one needs to hear about sad times.

I had watched the movie “Fiddler on the Roof,” filmed in Croatia, and I knew she was FROM Croatia, so for years that became my idea of her childhood: village life, horses and carts, headscarves on the women, and at the end, a big trip to America.

Eventually, Rose dictated a letter to my grandfather (her son) about her life, just for me. I don’t have the letter now, but I remember my pride and awe in getting it.

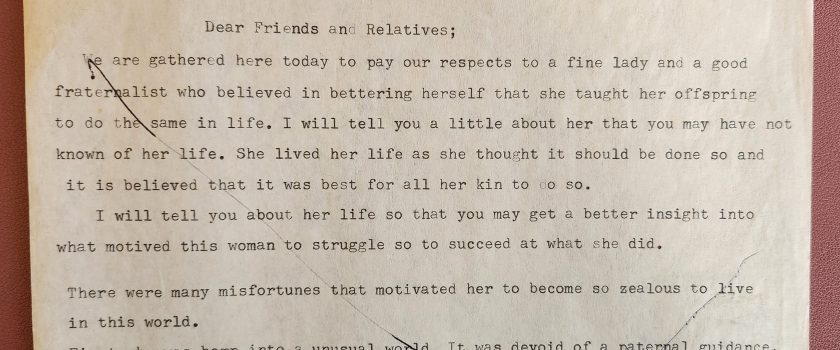

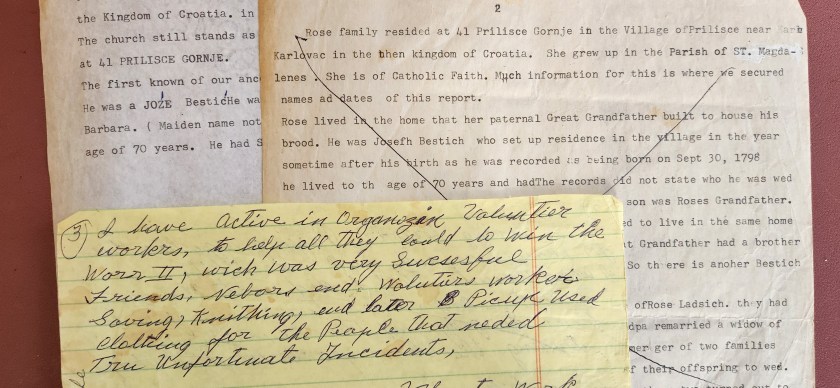

What I do have is a handful of her own notes. Reconsidering silence, Rose evidently tried writing or typing bits of her story, even crafting a eulogy for herself. They are particularly distinctive because Rose wrote in the third person, about herself, in a voice that aimed for as much grandness as her English and her typing skills allowed.

Over and over in her notes: “no stranger to hard work”; “she was a hard working girl who did not shirk hard labor”; “worked for everything”; “always paid our insurance and only used it once.” She would want you to know none of what I’m telling, but she would want you to know that.

4. All Hard Work and the Rewards Were Small

Decades before the house on Hull Street, with its peonies, its handmade doilies, its crock of sour cabbage in the basement, there was a farm where Rose learned how to do that.

Rose’s early life was a little like “Fiddler on the Roof.” Catholic rather than Jewish. Croatian instead of Russian. No pogroms. But the tenuousness and strain of an agricultural life, with poverty always held at arm’s length—that was probably much the same. She sums up their life in one of those drafts: “All hard work and the rewards were small.”

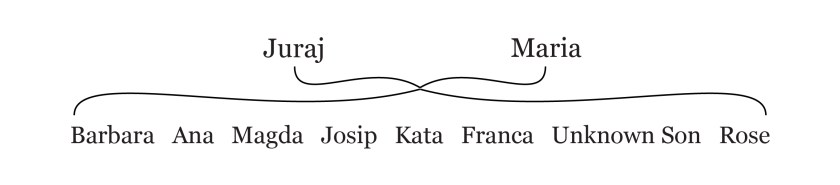

Almost a century before her birth, one of Rose’s great-grandfathers established a zadruga, a collective farm that was common in this region. It requires sufficient farmland and large buildings to support multiple or extended families, who all work to keep it going. The zadruga was the center of life for her grandparents, and then her parents Juraj and Maria. It succeeded for many years, until it didn’t.

From Rose’s notes, roughly translated:

“[The zadruga] is shrinking, father and mother work as hard as they can, but it is excessive

father worked excessively at the farm and mother, along with a friend who still lived in the house

father fell ill and had a chronic fever for 3 days with domestic help and a home remedy, they called a healer from Karlovac but it was too late

The widowed Maria was left a failing farm and 7 children—and she was pregnant with Rose. Maria would later tell Rose that she had tried lifting heavy rocks, hoping that it would cause a miscarriage. But, Maria said, she now felt that God was punishing her for doing so, and his punishment was that Rose had grown up to be so wonderful.

(“Your wonderfulness is proof I’m being punished” is a…complicated way to parent.)

Given all that, it’s unsurprising that Rose was raised more by her sisters, particularly her sister Kata. She learned to cook, bake, sew, garden—and she did it well. Just one anecdote survives: Rose once got in trouble for using her schoolbooks as a sled on snowy hills.

It helps to know that Rose made fun for herself because childhood went quickly. Her dear Kata died in 1908. And in the summer of 1910, Rose boarded a boat bound for the US. She would not be back for 40 years.

5. The Train to Gary

Another legend, this one from that letter Rose dictated for me.

The plan was that Rose would go live with her older brother Josip (Joe), already established in the US. She would travel from her village of Prilišće to New York, then go to Pennsylvania where Joe and his family lived.

Her notes, so painstakingly corrected, never mention whether she was given any choice about the move. Truth is not just where our stories cross, but also in the silences.

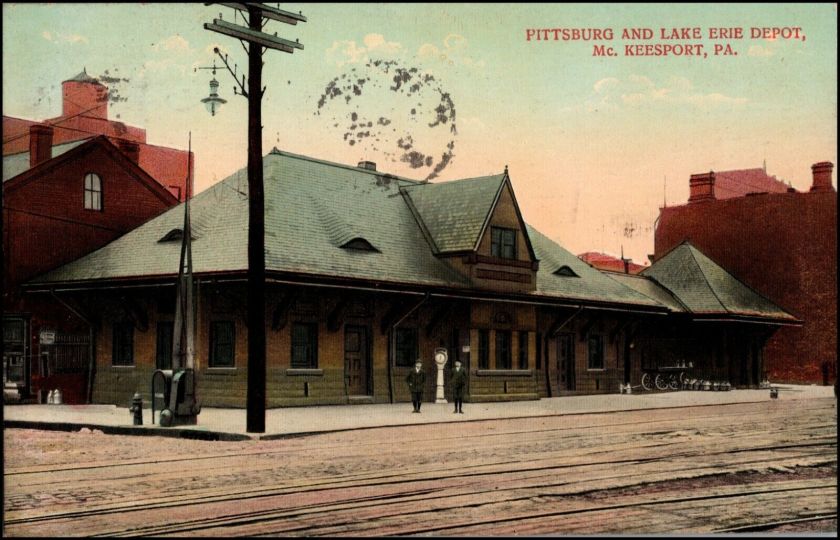

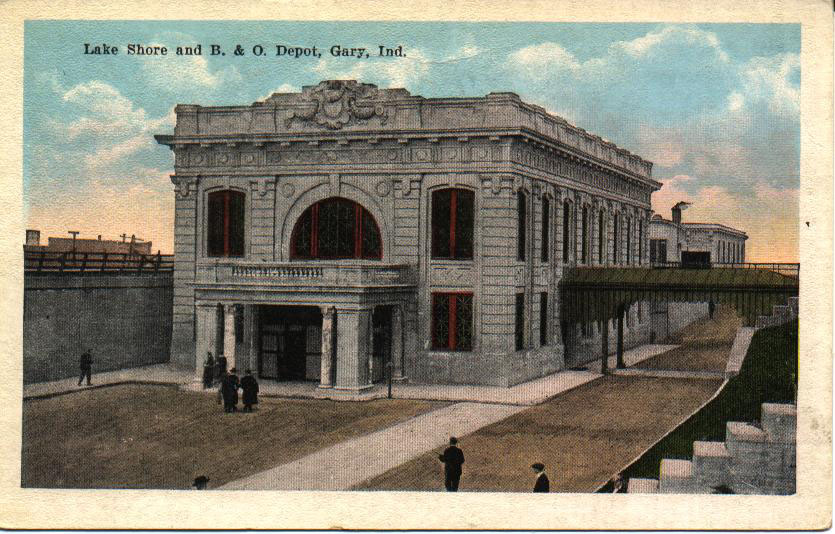

Rose made it to McKeesport, PA, only to arrive and discover that Joe had already moved to someplace called “Gary, Indiana.” She was 15 and spoke almost no English, but she boarded a train—alone— and made it to Gary, where she found Joe and his family.

It’s hard to describe the effect this story had on me, how it rang in my soul, especially because I was only a few years from that age myself. It has lived in my head for decades as a reminder of what I might be capable of—but also the mark I am forever missing.

What effort in my life could possibly compare?

6. Amerika

Lay the records against the legend. Find the truth in there somewhere.

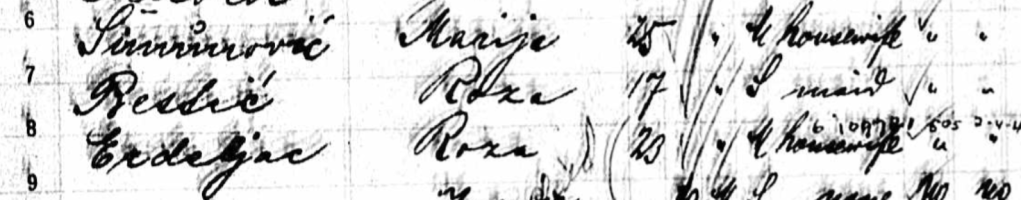

Because now I do have records. I can see that the boat trip wasn’t done alone—Rose came with other people from her village. But that same document says she was 17, when she was actually just 15. A careful lie? A shaded truth to help her odds of being allowed in? Another silence.

I also understand that her trip from McKeesport to Gary was likely more than I imagined. There was a large Croatian community in that part of Pennsylvania. A friend of a friend, a distant cousin, a knowledgeable person—someone could have put her on the right train with a packed lunch and clear instructions. I hope it was that easy, even as I now understand how it must have been daunting, boring, confusing, lonely, exhausting.

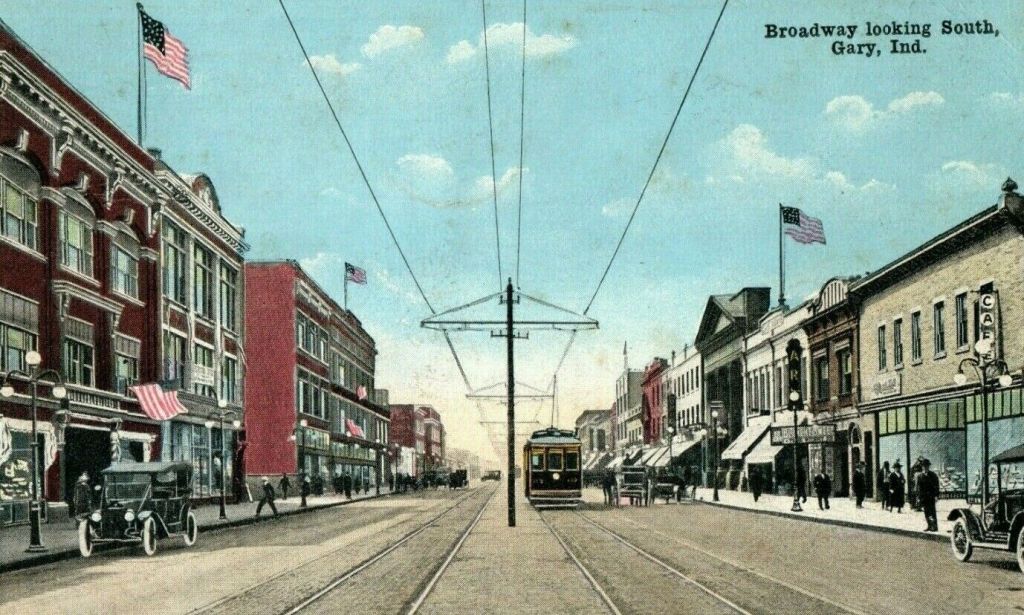

Joe emigrated in 1900, so Rose hadn’t seen him since she was 5. But he was now in charge of her life, her de facto parent in the US. Rose lived under Joe’s watchful supervision, but she was allowed to ride the streetcar by herself. Prilišće must have seemed like a distant planet.

And yet, the village was here. Between Chicago and Gary there were already about 30,000 Croatians, a thousand times the size of Prilišće. There were two Croatian newspapers. Gary had its own Croatian orchestra.

Croatians were filling the steel mills and building churches, but they were also getting in gun fights and losing their children on the front page of the paper. America was full of promises, but edged with glittering danger. A young girl could go very wrong.

Joe helped her find a job in a pickle factory, and then as a maid for a wealthy Jewish family in Chicago. The girl from the farm began earning $3 a week and had weekends off. She kept her head down, her hands busy.

All hard work and the rewards were small. ☗

© 2025 Tori Brovet/All rights reserved. GraveyardSnoop — at — gmail.com.