I’ve been going through The Boxes and trying to provide some coherence to a 10-decade salad of manuscripts, notes, photos, and letters. Acid-free sleeves and PVC-less binders are being employed. Photos are gradually moving into acid-free envelopes, and labels are being affixed.

Emphasis on gradually. It’s slow-going, and I’m already tired.

The whole process is slower precisely because of the disorder, and because of the randomness of what was saved by someone at some point. All those decision-makers are conveniently now dead, and I am left to make sense of their choices. No one can explain to me why they saved 50 blank postcards, but only one photo of my great-grandmother.

I hope they enjoy their waiting room, because it’s gonna be a while.

****

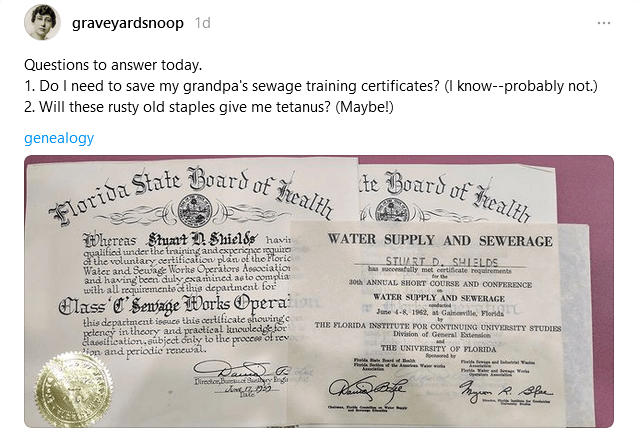

I alluded to some of this yesterday on Threads, asking out loud if I should save these sewage training certifications my grandfather earned in the 1960s.

The replies were pretty much unanimous: Save them! Scan them! Save everything! Save it for the future!

Here’s the thing (and this is not to slight anyone—everyone makes different choices)…

I appreciate the motivation and the thought behind “Save everything!” I genuinely do. There are things I WISH had been saved for me, and no one thought to do so. I wish that all the time.

Part of the reason I now have this mess in my living room, for good and bad, is because of people who thought they were saving everything. Which is why I had three drafts of the same family history, but no photos of people from an entire branch of the tree.

It’s also complicated because many of these papers were created by my great-grandfather, James K. Shields. He was the first family genealogist, but also a well-known pastor and Anti-Saloon League superintendent. And a writer. And for a short while he ran a movie company.

From him there are family history drafts, letters to Congress, notes for speeches, notes for things he wanted to put in books…None of it is complete, and all of it is unsorted. Or partly sorted. Or multiple drafts of the same writing.

The hard truth is, I don’t think all of it needs to be saved.

If you have a pile of unsorted papers and mail and photos in your house, picture that. Now imagine that stack gets stuck in boxes for decades, and then is handed off to someone born a hundred years after you. Yes, they would get an understanding of you, but would it be an accurate one? Would everything in the stack be worth saving forever? Would it all be worth the expense and time to scan or sleeve and store everything? And remember, it’s not your effort being expended—it’s that future person’s effort.

That is where I’m at.

****

As a childless person, hearing that I should save for future generations carries a particularly sad sting.

The very notion of passing down to your kids… is a privilege reserved for those who have kids. The rest of us are not so lucky.

This branch is my mother’s. She was an only child. Of her three children, I am the most involved in this work. I’m pretty much the end of the genealogists in our family, and the few people that are left—for reasons that are personal and private to them—are unlikely to be interested.

I am it.

If genealogy processes are going to stay relevant, they need to make space for people who don’t have children. Telling folks to save for future generations is not going to resonate for increasing numbers of people.

****

Some things, like my great-grandfather’s Anti-Saloon papers, I can find a place for. My task is to get those items into an archive. Those things can matter to many people.

But these sewage certificates only mattered to my grandfather Stuart, for a short while, and he died in 1975. I ultimately decided to keep them as proof of what a checkered professional life he had.

Stuart did not plan to be a sewage engineer. It appears to have been the fallback job after he was laid off from Pratt & Whitney in 1959, a move motivated by anti-union sentiment. So the sewage job was not wished for, and not long-lasting.

Further, from what I can tell, I think he did that sewage engineering at a notorious reform school in Florida. It was not a happily remembered situation.

Before that he worked for a tire company, trained as a chiropractor, and spent almost a decade as a window-dresser. He was all over the map.

So I’m saving them. But I also know I am probably the last person on the planet who will ever care about them. The value we imbue to objects and papers rarely outlives us, and that has to be OK.

I am learning to be OK with it. ☗

© 2024 Tori Brovet/All rights reserved. GraveyardSnoop — at — gmail.com.

I have my grandmother’s beauty operator’s license, and that’s meaningful to me, but perhaps to no one else. The goal is to complete an archival scrapbook about her, with instructions to my family to donate it to the Josephine County Historical Society when they don’t want it anymore. This little card will go into the book, but I also scanned it for Ancestry.

I think those certificates are really interesting from the standpoint of his whole life, which may end up consolidated into one binder. That will be interesting for sure someday.

Candace

LikeLiked by 1 person

oddly enough, I had been thinking about this issue of next generation saves. You are absolutely right. On the other hand, I think if would be great if someone ( hint, hint Tori Lyn) would create a large system whereby people could download significant pieces of family history under their name. But it would be a repository anyone could add to or look up and read. Like a family histories Facebook. Janice

LikeLiked by 1 person