Read the full Cora Stallman series here.

I have had a long time to think about Cora Stallman.

Over years, whether during the periods of all-consuming research, or the lapses when I put her away, I’ve been turning this case over in my head. I’ve asked myself every what-if imaginable — even the unimaginable ones. I’ve considered the people, the town, and the fields that stretched around them.

Mostly, I’ve treated this story like a kaleidoscope, twisting it this way and that, watching all its many elements fall into new patterns and form new theories.

All of this is a long-winded way to say: Despite everything I know, I’m still unsure how Cora died.

I don’t think Thomas Seaman killed her. I think it was an accident…for reasons we will unpack down the road.

Her presence in the cistern, though, could not have been not an accident. Despite what Tom and Bos Lilley said about “copious” amounts of water coming from Cora’s mouth, the autopsy was conclusive that she had not drowned. She had no water in her lungs, no bronchial mucus that comes with drowning. She was dead before she got in the water — or at least, not because of it.

Which would mean that someone placed her there.

There was only one other person on Anna Seaman’s farm that night. After Oscar and Eunice Seaman (Tom’s nephew and his wife) left shortly before midnight, it was just Tom and Cora on the farm until she was pulled from the water at sunrise. And when they left, Cora was alive.

Of all the moments to consider in this story, these dark hours on Saturday morning are the ones I wonder about the most. There is six hours of blackness between Oscar’s car pulling away, and Bos getting an early-morning knock on his door, with her death happening at some moment in the dark.

So what happened?

Maybe it was exactly like Thomas said. I have to allow that he might not be lying. Cora made up his bed for him. He went to sleep, got up for milking, and then began the search that ended outside the cottage as the sun arose.

But I also have to consider that he might not be honest, or that he settled for a variation on honesty.

Maybe he got up, found that the previously sick Cora had died while he slept, and he panicked. He wasn’t supposed to be on the farm at all, and now this.

Or most terribly, most sadly, maybe Cora took her last breath in front of him. Perhaps, as testified, she was improving when the Seamans left — and once it he was alone, it all went wrong.

Did he sit in the silent cottage, mute with shock? Did he reach for her hand?

Did he decide that creating a lie would be better than admitting the truth of her death, and thus their relationship? Because someone put those letters in the cistern and the sign on the porch. And if it wasn’t Cora, or a convenient and mysterious stranger, he is the likely suspect.

Turn this way. Turn that way. Try to see a pattern. Watch the pieces fall together.

No matter how I twist it, the same two elements keep glimmering brighter than anything else: She didn’t drown. He was the only one there.

* * * *

So then the question becomes, Was Thomas the kind of person to obscure a death and lie about how it happened?

It’s a fool’s errand to try to know someone through 90-year-old newspaper stories — not that I’ve never let foolishness stop me before. I continually try. I will grasp at any flare of personality or character that shows itself in these articles. If I can know these people even a little bit, that’s something.

For Thomas, I see a possible clue early in his inquest testimony: “The home on my farm is just as my first wife died and left it.”

That woman, too, was a Cora — Cora Hutton Seaman, his wife for nearly 20 years until she died of tuberculosis in 1916. He married Anna Stallman three years later.

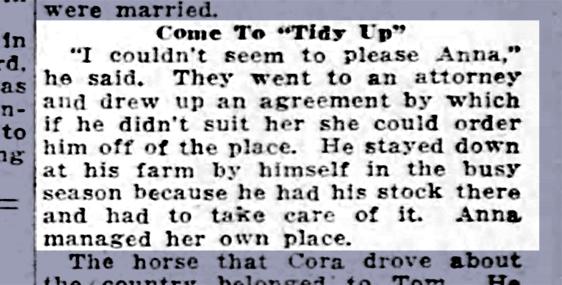

And a mere three weeks after that, Thomas and Anna were at a lawyer’s office, legally separating their two properties. This is the “arrangement” Anna first denied, and then they both had to concede actually existed. There had “been a disagreement” — and that was all they would say.

It’s such a nothing comment, and yet so poignant upon inspection.

Blending two households is more fraught when you are older. Memories come with the furniture. If Tom hadn’t altered any of it by August 1925, almost a decade his first wife’s death, how much harder was it only three years after she died, even for his new bride’s sake?

Once their relationship is placed in this light, everything shifts. Anna, who had seemed cold and remote, now becomes the spinster who finally got married, then quickly learned that there was no space for herself in her new husband’s home, and he wouldn’t (or couldn’t) make one. Thomas becomes the widower trying marriage too soon, only to discover that grief might not be done with him.

Both sides of that are heartbreaking, but I feel for Anna the most here. She spent a decade keeping her elderly uncle’s farm afloat and tending to the old man himself. Whatever her heart might have wanted, she put it aside in favor of harsh practicalities. And yet, once she did get married, it was effectively over almost immediately.

Whatever the true cause of their division, the solution was a fenced-off domesticity, where Thomas would change nothing in his own home, and Anna would keep her farm off-limits to him. But he would still come to her house for dinner every night, and they would maintain the outward appearance of a marriage. Even their family wasn’t told about the separation.

And then, around 1921, a new, younger Cora arrived — Anna’s sister, Cora Stallman.

As both Anna and Thomas explained, Cora traveled between the two households and worked at both. At Anna’s she kept the farm’s accounts, worked with the field hands, and had the run of her little cottage. At Thomas’ home, she did wife’s work. She cleaned and swept his place, handled his correspondence (ordering a baby buggy for his new grandson), and even borrowed his horse for errands. When dinner was done, it was Cora who walked Thomas home each night.

For all their carefully laid boundaries, legal and otherwise, Anna and Thomas created a situation that required Cora to cross them every day. Hurt feelings and disagreements were inevitable. And if Cora and Thomas were emotionally involved, the atmosphere would have been that much more charged. In her few released diary entries from the previous fall, Cora writes about Tom being cross. In December, she notes, “His face was angry and he gave no pleasant look.” There’s a “row,” and a few days later, a “great struggle.” She describes being in a “quandary as to fate” — presumably her own. Something full of emotion and uncertainty was consuming her thoughts, and it spanned months.

Was Thomas the kind of person who would lie about Cora’s death? I don’t know.

Was he the kind of person who would cross a boundary and then lie about it? I think he might have been.

I think Cora might have been, too.

* * * *

Whatever Thomas really thought, and whatever truths he tucked away, the rest of his inquest testimony was matter-of-fact and unemotional.

He rose around 4 AM on Saturday, to milk the cows. He thought he heard Cora clear her throat in the bathroom.

When he returned with the milk, she wasn’t anywhere in the house. He searched “from basement to attic,” without luck. He called for her and got back only silence.

He headed to Bos Lilley’s, asking him if Cora was there. Back at the house, they searched it again, then the coal house and the wash house. Only then did they try the cottage, where he said the shades were drawn and the door locked. Neither of them noticed the sign on the porch.

He spotted the cistern and — in what sounds like lousy B-movie foreshadowing — said to Lilley, “I hope she ain’t in there…”

The rest played out as had already been told.

No, he knew “nothing about the diary nor it’s quotations or signs.” He didn’t even know she kept one.

No, he didn’t know why she wrote about him so much.

No, he had no relationship with her beyond family.

And with that, Thomas Seaman was done. His secrets stayed kept.

* * * *

The inquest testimony, too, was concluded. However, Coroner Schilling was not finished just yet. Before handing the case to the grand jury, he had lab results to disclose.

After the weeks of kerfuffle and fussery about forensic testing and whether Coles County would pay for it, it turned out that Cora’s organs had been tested after all. ☗

Next time: The one little thing that ties it all together.

Sources

Decatur Herald; Sept. 1, 1925

Mattoon Daily Journal-Gazette; Sept. 1, 1925

© 2019 Tori Brovet/All rights reserved

This is a fascinating account! But why did Cora have to walk him home?

LikeLike

I have wondered that myself! No one ever explained why, especially since he lived very nearby. But even Edith Lilley mentioned it, saying she watched them walk down the road every night until the corn grew too high to see them.

(I love that line, by the way. You can practically see her curtains twitching as she watches them.)

LikeLike

Haha, yes, I can see that! Oh, that really is strange. No reason for her to do that unless there is some hanky panky or he has a deficiency that means he can’t walk by himself. Or there is something she has to do there every night. That is maybe the strangest thing of all to me.

LikeLike