Read the full Cora Stallman series here.

Friday-Sunday, Aug. 7-9, 1925. Coles County, IL.

On Friday morning, Edith Lilley hit her limit.

The question of how Cora Stallman did, or did not, die had hung over the Lilleys’ farm for a week. It pulled Edith’s husband, Bos, out of bed early the Saturday before, and brought him hustling back home for the telephone. It barged into their conversations and upset their schedules. It kept both of them from sleeping.1 It was a heavy summer haze, hanging over everything. A body could hardly move under it all.

And now, the reporters were in Edith’s yard, trying to make it about her.

She’d already been interrogated by the sheriff. Did she, Edith Lilley, mastermind a series of harassing and anonymous letters? Had she been to the Humboldt post office last Friday? Did she buy stamps? Did she send the last letters? Did she know Cora? Were they friends? Was Cora maybe TOO friendly with Edith’s husband? Did she raise a row about it?2

Enough already. These newspapermen were not getting on her farm.

The flock of reporters was smaller now; most out-of-town papers had called back their correspondents. It was left to the local press and some remaining wire services to eke anything new out of this story.3 Edith, with her temper, made for good reading.

“Don’t you dare come inside this yard!” she warned them. She would answer their questions — but only grudgingly, and from the border of the property.4

NO, she didn’t write any of those letters. She didn’t kill Cora. She didn’t know anything about how the woman had died.

“Anyone who said that I bought three stamps lied,” she shouted. “They accuse me of killing this woman. I didn’t have anything to do with it. Why should I kill her?”5

No, Cora’s sister Anna Seaman — her husband’s boss, and the landlord of their tenant farm — hadn’t told Edith what to say, or to stop talking about the case.

Yes, she had been in the Humboldt post office, and yes, she had mailed a letter — to her sister in Arkansas.

Investigators had traced some of the paper used in the letters to a store owned by Edith’s step-grandmother. What about that? I didn’t send them, Edith repeated. She didn’t know anything about it.

Cora, she claimed instead, was her neighbor and friend. She felt that Cora was probably insane, and had written the letters herself — but Edith liked her well enough. There was no grudge here.4, 5

* * * *

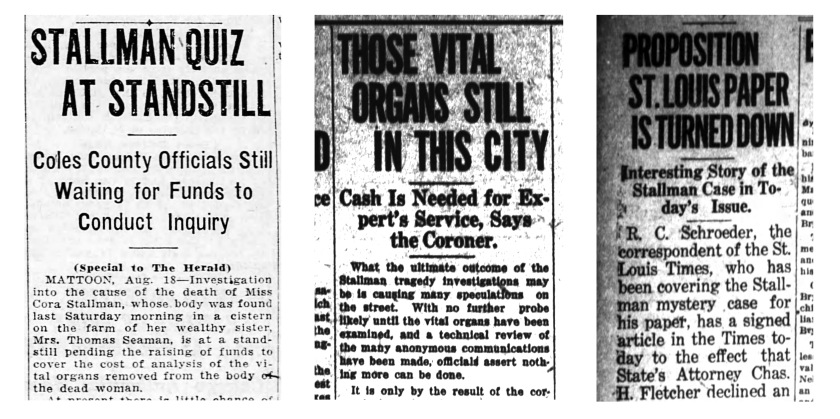

Writing about Edith was probably a welcome change from the frustrations of the forensic case. The investigation had a stick in its spokes: Money. There was still no provision for paying for forensic tests on Cora’s organs or the letters.

Coles County would need $450 in cash to start tests at the University of Illinois. It would cost another $150/day to bring the experts to Mattoon for their testimony.3, 4

The cash aspect was an unfortunate reality. Testing labs, having been burned by false promises from delinquent county supervisors, did not work on credit. It was either payment in advance or a cash guarantee.4

State’s Attorney Charles Fletcher tried to work around this, arranging a special meeting of the county board of supervisors just for this situation. But according to the Coles County Treasurer, Arthur C. Shriver, there was simply nothing in the bank to pay for forensics — he hadn’t even paid the county’s April bills yet. There were no funds to appropriate, he told them, so voting would be pointless. The meeting was cancelled.5, 6

Fletcher suggested an alternative, more cursory inquest, based only on the facts known and without specifying a cause of death. Coroner FS Schilling was not in favor.3

The reporters wondered out loud whether Schilling or Fletcher could put up their own money for the tests, as other counties had done.3 Schilling shot this down. “I certainly do not intend to guarantee payment or advance money in these cases, and I do not blame the State’s Attorney for not doing it. Why should we do this more than anyone else?”3

Without funds, there could be no test results. Without the results, the inquest couldn’t conclude.3, 5

Whatever answers were tucked away in Cora’s viscera, they would stay hidden.

* * * *

With no news from the investigators, reporters were left to peck among sparse kernels for any news. They had two new items to consider — and the first one really should have raised more questions. I am mystified that it didn’t.

It was already well known that Cora had been sick/nauseated/delirious for a day before she died. Her brother-in-law, Thomas Seaman, had supplied multiple versions of what had happened that last night, particularly who slept where (she was in her farm cottage; I was in the cottage; I was on the porch; she was in the main house).

Thomas and Cora were indeed in the cottage that night — and not alone. Early articles said that Thomas’ brother and his wife had come for dinner. In fact, it was Thomas’ 23-year-old nephew, Oscar Seaman, and his wife Eunice. They had been with Cora and Thomas, in the cottage, until nearly midnight on Friday. Cora died just hours after they left.4

It was hardly a dinner party. In some unspecified way, they were tending to an ill Cora. According to Eunice, Cora was “very nervous” and fearful about a man she did not name. She asked for water more than once. The papers were quick to note that thirst can be a symptom of poisoning, and that Cora had a pitcher of water next to her bed.

And yet, it doesn’t seem like anyone followed up on this. No group of reporters showed up on Oscar and Eunice’s doorstep to pepper them with questions. It’s not even clear if the sheriff’s department investigated further. Their story seems to have been accepted in its entirety.

The weekend’s other new detail came from Cora’s undertaker. Ira Mulliken had already noted that when he was called to tend the body, Thomas was distraught (“Oh why did this have to happen when Anna was away?”). Now Mulliken added that Thomas was “wringing his hands and sobbing” at the scene.4 And when he arrived, no doctor or coroner was there, but Mulliken’s assistant, Bessie Bolin, already was.

“[Thomas seemed surprised that the coroner should have to be called, but he finally asked me to summon him,” Mulliken said.4

Again, no one followed up.

* * * *

The newspapers opted for advocacy as a way to stir the stagnating investigation.

The St. Louis Times made a public proposition: It would pay for the testing. Schilling reportedly “jumped” at the chance, quickly arranging to stay with the evidence during testing in St. Louis, escorting it to and from Illinois. However, Fletcher balked at having Cora’s organs taken out of state. The offer was declined.3

When Fletcher tried to keep the suicide option open, claiming he had two new leads, even the pro-Seaman-family Mattoon paper was skeptical. “[There are very few people who now express the thought that Miss Cora Stallman committed suicide. … It is generally believed in Mattoon, Humboldt, and that vicinity that a master murder has been committed in this case.” The paper offered two popular if unlikely theories: 1) Some man poisoned her, or 2) The murderer waited for her to die, then put her in the cistern.4

The Mattoon paper also started to counteract notions that Cora had written the letters (“No one now believes these emanated from Miss Stallman…”), or that she was insane — an idea the paper itself had pushed.

Local doctor Thomas Morgan was called on as character witness: “Miss Stallman was no more insane than I am today. I have seen her repeatedly and talked with her. She was always kindly, thoughtful, and generous.”4

Dr. Morgan was not alone. According to Coroner Schilling: “Nearly every citizen of Humboldt, which she frequented so often, wants to testify. And nearly every citizen of Humboldt, outside of the Seaman clique, has told me that Miss Stallman was sane and that he believed the woman was murdered. I want every one of them to appear and testify.”3

“Outside of the Seaman clique…” No one could have failed to miss his point.

Not to be outdone, the Decatur paper took Coles County to task in a biting Sunday editorial.7 The public money squabble, with a possible murder hanging in the balance, was becoming a public embarrassment.

You can read the full editorial here. It doesn’t hold back.

I see a second implication. By ruling for suicide, and avoiding expensive tests, the county could save hundreds of dollars. If it meant avoiding a public and complicated murder or manslaughter trial, they might save even more.

Was that a thought in their heads? I have no way of knowing, but I do wonder. ☗

Next time: Who is fighting for Cora?

Sources

[1] Mattoon Daily Journal-Gazette; Aug. 4, 1925.

[2] Streator Daily Free Press; Aug. 6, 1925

[3] Mattoon Daily Journal-Gazette; Aug. 8, 1925.

[4] Mattoon Daily Journal-Gazette; Aug. 7, 1925.

[5] Decatur Herald-Examiner; Aug. 7, 1925.

[6] Decatur Herald-Examiner; Aug. 8, 1925

[7] Decatur Herald-Examiner; Aug. 9, 1925

© 2019 Tori Brovet/All rights reserved

One thought on “Cora: How Deceptive Appearances May Be (7)”